Kristofer Schipper, Influential China Scholar, Dies at 86

A native of Holland, he helped change the understandingof Chinese religion and became a Taoist priest in the process.

By Ian Johnson

April 4, 2021

An altar painting of the Dutch scholar Kristofer Schipper inXuanmiao Temple Suzhou in China. He became a Taoist priest in the course of hiswork. by Tao Jin

Early in the afternoon on Thursday, in the southern Chinese city of Suzhou, more than 50 people gathered in a Taoist temple for a 10-hour ceremony to bid farewell to one of the most influential China scholars of recent times.

But this wasn’t to honor a professor at one of China’s great universities; instead it was for Kristofer Schipper, a Dutch Sinologist whose work helped usher in a fundamental shift in how people think of Chinese religion and society.

Professor Schipper died at 86 on Feb. 18 in Amsterdam after developing a blood clot in his stomach, said a friend and former student, Vincent Goossaert.

Professor Schipper had made Taoism his life’s work, helping to elevate it from a widely disregarded faith to a religious tradition that is regularly included in global discussions of current issues like climate change.

More important, his ideas contributed to an understanding of how Chinese society has been organized through its history — by local autonomous groups often centered on temples rather than the emperor and his vaunted bureaucracy, as historian shave traditionally tended to depict it.

An ordained Taoist priest, Professor Schipper combined firsthand knowledge of rural religious life with deep textual study of classical Chinese.

“He was ableto show that there was a religion of the people of China that was deeplyconnected to local forms of self-organization and self-government,” said Kenneth Dean, head of Chinese Studies at the National University of Singapore. “It was part of a change in how people described Chinese society.”

Professor Schipper is best known for his book “The Taoist Body” (1994), which was written for the general reader. It shows how many seemingly disparate elements of Chinese culture — martial arts, art, cuisine, rituals, holidays, medicine and much local religious life — are imbuedwith Taoist concepts. That helped broaden how Taoism is defined, from being known for a few philosophical texts and local religious practices to being seenas encompassing a huge swath of Chinese culture and society.

Among scholars, Professor Schipper’s most influential work was as co-editor, with Franciscus Verellen, of a monumental three-volumework, “The Taoist Canon: A Historical Companion tothe Daozang.” Totaling 1,800 pages, it was the first time that the1,500 core texts of Taoism were systemically arranged and described. Theproject lasted nearly 30 years and involved dozens of scholars from around the world — an effort that many say created the modern field of Taoist studies.

A portrait of Mr. Schipper, left, and hisTaoist master, Chen Rongsheng, in Taiwan. Family of Kristofer Schipper

Kristofer Marinus Schipper, who was known as Rik, was born on Oct. 23 1934, in Schardam, a rural town north of Amsterdam. His father, Klaas Abe Schipper, was a Mennonite pastor, and his mother, Johanna (Kuiper) Schipper, was a devout believer. Their religious convictions inspired the couple to hide Jews during the German occupation of Holland in World War II.

His father was detained and interrogated twice, each time for several months. His mother fled to Amsterdam, taking young Rik and several Jewish children to hide in safe homes.

The family survived the war, but his father’s health suffered, and he died in 1949 at 42. (For their efforts on behalf of persecuted Jews, the couple were later declared “Righteous Among the Nations” by Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust remembrance center.)

The wartime experience had a profound effect on Professor Schipper.

“This really shaped his worldview, both his hatred of nationalism and his deeply humanistic preference for local democracy instead of great national narratives,” said Professor Goossaert, who teaches religious studies at the École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris. “That’s how he read Taoism.”

Professor Schipper came to that realization slowly. He moved to Paris to study with the French Sinologist Max Kaltenmark, one of a series of French scholars who took Taoism seriously. Most academics, however, focused on the more traditional philological study of deciphering often-obscure Taoist texts.

In 1962, Professor Schipper went to Taiwan to study at the Academia Sinica and, according to a story he liked to tell his students, was told that Taoism did not exist as a religion.

Yet in townsand villages he encountered Taoist temples where priests were using texts fromthe Taoist canon in ceremonies. They had little formal education but had learned classical Chinese from their masters, often their fathers; they belonged to a school of Taoism that was passed down patrilineally. Some of the priests had lineages reaching back 1,000 years, evidence that the religion ofantiquity and the present were linked.

Professor Schipper realized that he had to be a participant observer and began studyingwith a Taoist master, Chen Rongsheng, in the southern Taiwanese city of Tainan.He was ordained a priest of the Way of Orthodox Unity, or Zhengyidao, school.

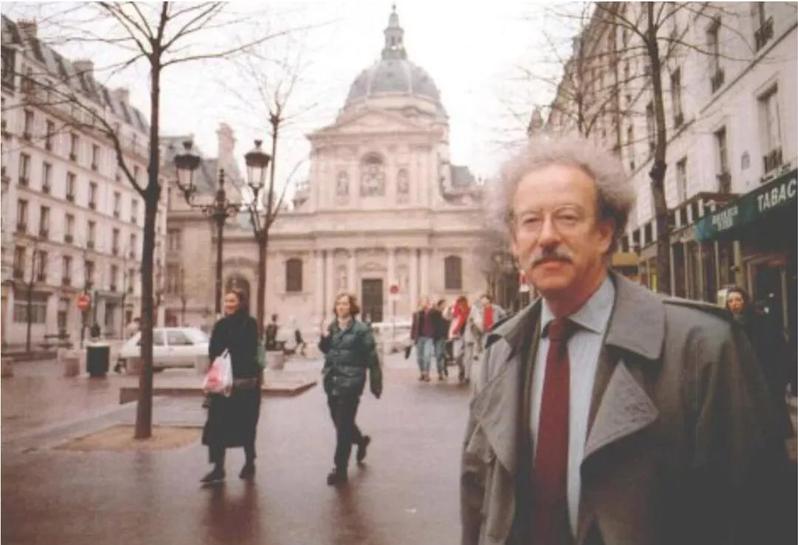

Mr. Schipper in Paris in the 1980s. Afterstudying in Taiwan, he became a French citizen and began researching the Taoistcanon. Family of Kristofer Schipper

After eightyears, he returned to Paris with a cache of ritual manuals that his teachershad given him. An ardent Parisian, he acquired French citizenship and took aposition at the École Pratique des Hautes Études, where he began systematicallyresearching the Taoist canon.

Professor Schipper was perhaps most influential through his students. An estimated 15 ofthem became professors of religious studies, but many dozens more went to Paristo be near him. He brought them into his orbit, invited them to live at hishome, gave them full use of his library, lent one of them his best suit for hisfirst job interview, and performed Taoist ceremonies when their children wereborn or when they got married.

Mostly, hesent his acolytes off to work on mammoth projects, like listing and documentingall the temples in Beijing, a 10-volume project that a decade later is onlyhalf complete.

His ideas onthe centrality of religion in Chinese history spread in the academy through hisstudents. Two of them, Professor Goossaert and David A. Palmer, wrote anaward-winning book that showed how traditional Chinese religion had beencentral to how Chinese society was organized, with temples functioning as across between cathedral and city hall.

The key rolethat religion played in organizing society helped explain why Chinese reformersfrom the late-19th century onward had attacked traditional religious practicesas part of an antiquated system that they felt was holding the country back.Their movement ushered in a wave of temple destruction that eliminated anestimated 90 percent of China’s religious infrastructure.

“Rik’s greatcontribution was to make us aware that the living religious tradition of ruralChina could be traced back hundreds or thousands of years,” said Michael Szonyi, head of the Fairbank Center forChinese Studies at Harvard University. “And this meant that Taoism isn’t‘feudal superstition’ but China’s indigenous religious tradition.”

Heling Temple on Mount Huotong in China’sFujian Province, where a funeralceremony was held for Mr. Schipper. by Tao Jin

Professor Schipper is survived by his wife, Yang Bingling and their daughter Maya, aswell as two daughters from a previous marriage, Esther and Johanna.

After retiring in 2003, he moved to the Chinese city of Fuzhou, where he established a library. He was highly influential in China, where his ideas spread.

“He said Chinese society was organized around many, many small temples,” said Ju Xi, an anthropology professor at Beijing Normal University, who counted Professor Schipper as a mentor. “So we have to understand how these temples organized people; then we can understand Chinese society.”

Professor Jusaid she was shocked when, a few years ago, Professor Schipper told her hislatest plan: to methodically list all the written material about all 108 holyTaoist locations in China and conduct exhaustive interviews with peopleinhabiting them — a project so vast that it could never be completed in hislifetime.

“Four days before he died, he phoned me for more than an hour and was still talking about how to research these holy sites,” Professor Ju said. “He was still thinking ofChina.”

The feeling was mutual. A temple among the 108 holy sites, Mount Huotong, held a funeral ceremony for him; the Suzhou temple held another one.

Tao Jin, an architect and Taoist believer, commissioned a local artist to paint Mr. Schipper in his Taoist robes. The painting was placed on the altar, and in along ceremony priests blessed Professor Schipper in the afterlife.

“He understood that Chinese religion is a living tradition,” Mr. Tao said. “So you need to understand it by talking to living people.”

Ian Johnson lived in China for 20 years. He won a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the country. @iandenisjohnson• Facebook